Author's Note: The "Upstate New York Stargazing" series ran on the newyorkupstate.com and syracuse.com websites (and limited use in-print) from 2016 to 2018. For the full list of articles, see the Upstate New York Stargazing page.

Upstate NY Stargazing in April: Comet hunting and the Lyrid meteor shower

Updated: Mar. 31, 2017, 6:04 p.m. | Published: Mar. 31, 2017, 5:04 p.m.

By Damian Allis | Contributing writer

In last month's article, we discussed the Messier Objects – bright galaxies, nebulae, and star clusters visible with little more than a quality pair of binoculars on dark nights. Charles Messier, the catalogue's namesake, may have had an interest in their origins and composition, but his real targets were the many comets just becoming visible to observers with what passed in the 18th century as "quality telescopes."

Those who know the story of "steel-drivin' man" John Henry can appreciate what technology has done recently to alter the rate of comet discovery by the professionals. Collaborative projects such as WISE, SOHO, LINEAR, and pan-STARRS have identified an unprecedented number of new comets in recent years while not intentionally comet-hunting! With cameras, telescopes, and even satellites set up to observe anything and everything, these missions are the first to observe new, distant comets before many, but not all, amateurs. So far this year, four new comets were discovered by amateur astronomers Elenin, Barros, Borisov, and Lovejoy. They may hear the gears of those astronomical steam drills being spun, but they certainly aren't ready to pack up and quit anytime soon.

There are many places online to keep up-to-date on comet discoveries and observing opportunities. Yearly predictions are provided by such astronomy magazines as Sky & Telescope, while much more information about missions and scientific findings can be found on the www.nasa.gov/comets website. Those wanting to take in comet discussion within the amateur astronomy community can even tune into CometWatch, one of many radio shows on the 24-hour astronomy and space science online radio station astronomy.fm.

April lectures and observing opportunities

New York has a number of evenly-spaced astronomers, astronomy clubs, and observatories that host public sessions throughout the year. Many of these sessions are close to the New Moon, when skies are darkest and the chances for seeing deep, distant objects are best. These observers and facilities are the very best places to see the month's best objects using some of the best equipment, all while having very knowledgeable observers at your side to answer questions and guide discussion. Many of these organizations also hold monthly meetings, where seasoned amateurs can learn about recent discoveries from guest lecturers, and brand new observers are encouraged to join and begin the path towards seasoned amateur status.

Announced public sessions from several respondent NY astronomy organizations are provided below for April. As wind and cloud cover are always factors when observing, please check the provided contact information and/or email the groups a day-or-so before an announced session. Also use the contact info for directions and to check on any applicable event or parking fees. Note that some groups will also schedule weather-alternate dates.

Astronomy Events Calendar

| Organizer | Location | Event | Date | Time | Contact Info |

| Adirondack Public Observatory | Tupper Lake | Public Star Gazing | Apr. 7 | 8:00 PM | email, website |

| Adirondack Public Observatory | Tupper Lake | Public Star Gazing | Apr. 21 | 8:00 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Senior Science Day | Apr. 3 | 3:00 – 4:00 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Night Sky Adventure | Apr. 18 | 7:00 – 8:30 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | AAAA Meetings | Apr. 20 | 7:30 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Octagon Barn Star Party & Lecture | Apr. 21 | 8:00 – 10:00 PM | email, website |

| Astronomy Section, Rochester Academy of Science | Rochester | ASRAS Messier Marathon | Apr. 1 | 7:00 PM – 1:00 AM | email, website |

| Astronomy Section, Rochester Academy of Science | Rochester | ASRAS Meeting & Lecture | Apr. 7 | 7:30 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Astronomy Section, Rochester Academy of Science | Rochester | Wolk Observatory Open House | Apr. 23 | 12:00 – 4:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | KAS Monthly Meeting | Apr. 5 | 7:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Lecture & Observing | Apr. 7 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Lecture & Observing | Apr. 21 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Lecture & Observing | Apr. 28 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Mohawk Valley Astronomical Society | Waterville | Public Stargazing @ Waterville Public Library | Apr. 1 | 8:15 – 10:30 PM | email, website |

The Northeast Astronomy Forum (NEAF) is happening April 8/9 at Rockland Community College in Suffern. This as the place for astronomers to be in April, where vendors from around the world will have astronomy gear for sale, several organizations make themselves available for information on such topics as astronomy outreach and light pollution, and frugal astronomers can take in two days of lectures and two afternoons of the NEAF Solar Star Party.

Lunar Phases

| New: | First Quarter: | Full: | Third Quarter: | New: |

| Mar. 27, 10:57 PM | Apr. 3, 2:39 PM | Apr. 11, 2:08 AM | Apr. 19, 5:56 AM | Apr. 26, 8:16 AM |

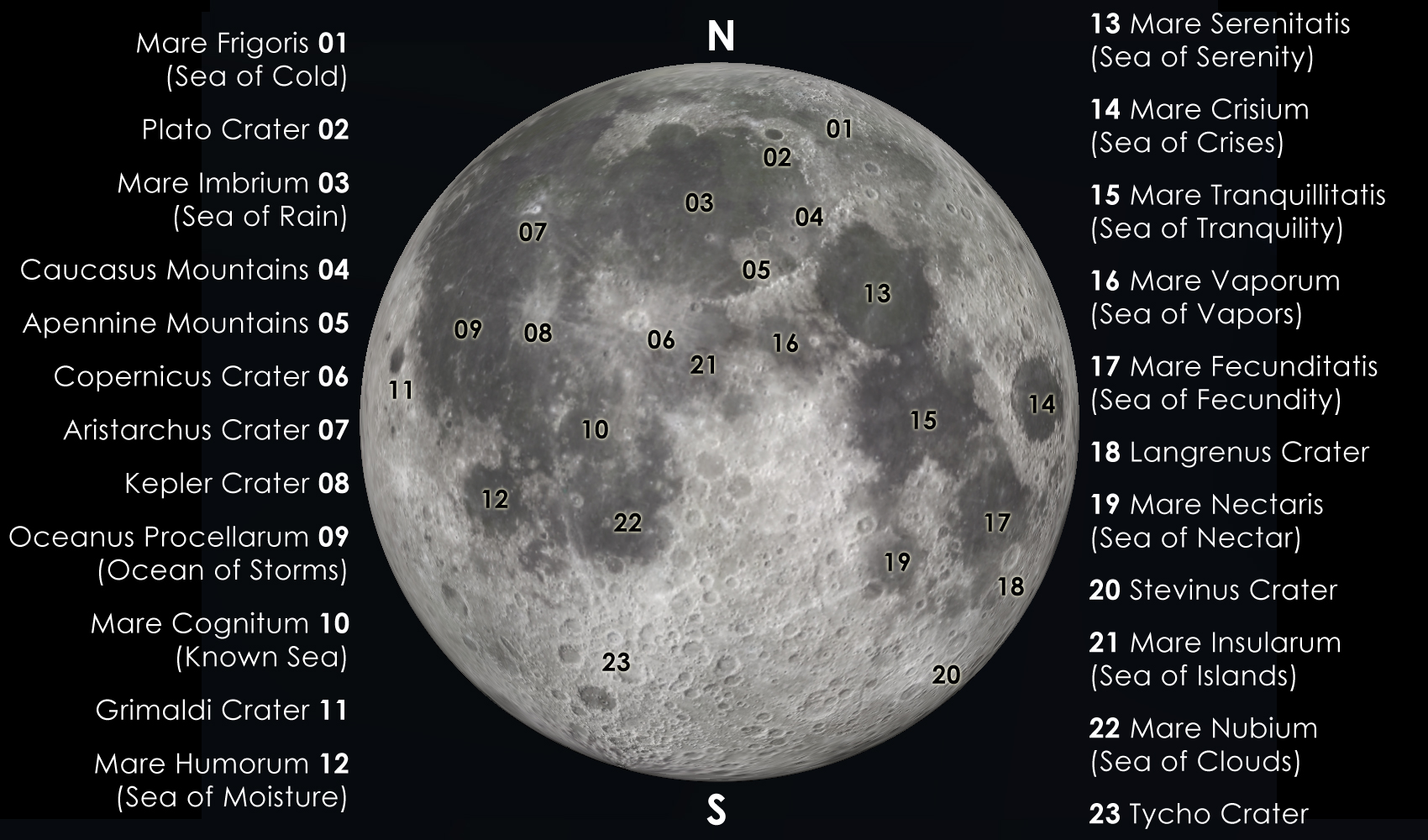

The Moon's increasing brightness as Full Moon approaches washes out fainter stars, random meteors, and other celestial objects – this is bad for most observing, but excellent for new observers, as only the brightest stars (those that mark the major constellations) and planets remain visible for your easy identification. If you've never tried it, the Moon is a wonderful binocular object.

Evening and nighttime guide

Items and events listed below assume you're outside and observing most anywhere in New York state. The longer you're outside and away from indoor or bright lights, the better your dark adaption will be. If you have to use your smartphone, find a red light app or piece of red acetate, else set your brightness as low as possible.

Southern Sights: There's a thin cloudy band in the southwest that runs through Canis Major, Monoceros, Orion, Gemini, and Auriga. That cloudiness is the plane of the Milky Way itself, filled with billions of stars. By comparison, the summer band of the Milky Way is much more pronounced and full of astronomical objects. Whereas we're looking into the core of the galaxy in summer, we're staring away from the center when looking at the winter/spring band.

If you want strong evidence that the Milky Way is a flat disk, you need look no further than the lack of that cloudy band in the direction of Leo, Hydra, and Virgo this month.

Northern Sights: The Big Dipper remains prominent in our nighttime sky, providing an easy marker for Ursa Minor and Polaris. To the east, the bright star Arcturus in Bootes (Pronounced Boo-oh-tes) is visible soon after sunset. Hercules and its bright globular cluster M13 also clear the northeast horizon in time for some late-night observing. See its discussion in the October 2016 article for M13's location.

Planetary Viewing

Mercury has swapped places with Venus as our early-setting planet this month, but its rapid motion will have it setting on or before sunset by mid-month. Your best chance to see Mercury is April 3rd, when it will set close to 9:15 p.m. After the first week or so, Mercury's light will be drowned out by the setting sun as it leaves the boundary of the constellation Aries. Mercury next graces our skies as a morning object that will rise very close to sunrise at month's end.

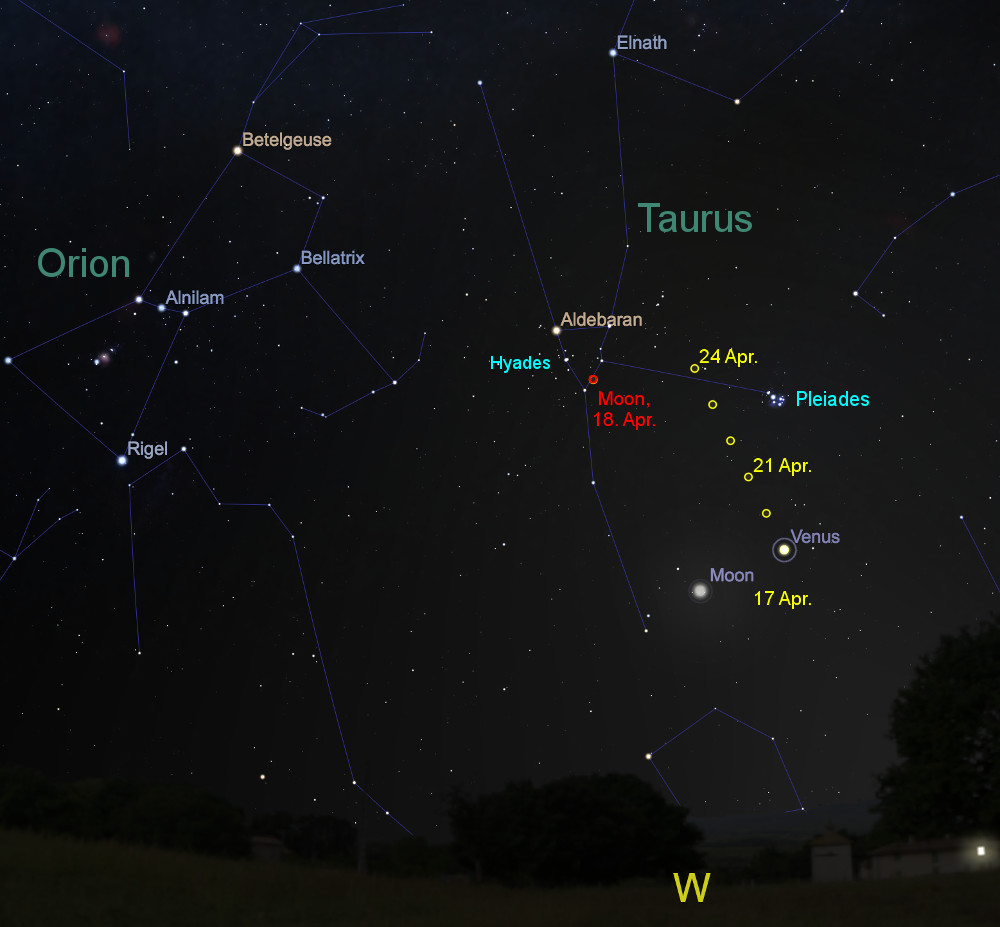

Venus has transitioned from being a brilliant sunset object in the west to an equally brilliant sunrise one in the east. It will rise a few minutes earlier each night this month, clearing the horizon around 5:45 a.m. on April 1st and 4:25 a.m. on the 30th. On the morning of April 23rd, Venus and a very thin waning crescent moon will be in close proximity, perhaps with a few leftover Lyrid meteors in the sky to coax observers out of bed early.

Mars remains an excellent target for late-evening observers, hitting most tree lines close to 10 p.m. each night this month. Mars begins with Mercury in Aries before moving into Taurus towards the Hyades star cluster. Mars will have one close encounter with the Moon on April 28, when some of the best of winter will all be clustered in the same piece of sky.

After sunset, you'll find the Moon just above Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus the Bull, then Mars between Taurus' head and the small Pleiades star cluster.

Jupiter clears the eastern horizon soon after sunset on April 1st and is already in the sky before sunset by month's end. Those looking to test their binocular aptitude can give a go at finding Jupiter in the pre-sunset skies this month – just make sure the binoculars stay pointed to the east and NOT anywhere near the setting sun.

Low power binoculars are excellent for spying the four bright Galilean moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – and several online guides will even map their orbits for you so you can identify their motions nightly or, for the patient observer, even hourly.

Jupiter and the very full Moon will come well within the field of view of a pair of 10×50 binoculars on April 10th inside the torso of the constellation Virgo and above the bright star Spica.

Those wanting to see Saturn this month will pay the price at work that morning. A very early riser throughout April along the border between Sagittarius and Ophiuchus, Saturn clears the southeastern horizon at 1:40 a.m. on April 1st and just before 11:45 p.m. at month's end. Saturn will more than make up for this in the months to come, when it will be ideally positioned during reasonable hours for all to observe from the beginning of summer until well into November.

ISS And Other Bright Flyovers

Satellite flyovers are commonplace, with several bright passes easily visible per hour in the nighttime sky, yet a thrill to new observers of all ages. Few flyovers compare in brightness or interest to the International Space Station. The flyovers of the football field-sized craft with its massive solar panel arrays can be predicted to within several seconds and take several minutes to complete.

April includes an abundance of flyovers in the first two weeks, then the ISS will disappear completely from NY nighttime skies until early May. All of the visible flyovers are bright enough to be obvious under clear skies, and seven April nights include the ability to see the station twice at roughly 90-minute intervals – the time it takes for the ISS to go once around the Earth. Simply go out a few minutes before the start time, orient yourself, and look for what will at first seem like a distant plane.

ISS Flyovers

| Date | Brightness | Approx. Start | Start Direction | Approx. End | End Direction |

| 4/1 | moderately | 8:53 PM | W/NW | 8:58 PM | NE |

| 4/1 | somewhat | 10:30 PM | NW | 10:31 PM | NW |

| 4/2 | very | 8:00 PM | W | 8:06 PM | NE |

| 4/2 | moderately | 9:38 PM | NW | 9:41 PM | N/NE |

| 4/3 | moderately | 8:45 PM | NW | 8:50 PM | NE |

| 4/3 | somewhat | 10:22 PM | NW | 10:23 PM | N/NW |

| 4/4 | moderately | 9:30 PM | NW | 9:33 PM | N/NE |

| 4/5 | moderately | 8:37 PM | NW | 8:42 PM | NE |

| 4/5 | moderately | 10:14 PM | NW | 10:15 PM | N/NW |

| 4/6 | very | 9:21 PM | NW | 9:24 PM | NE |

| 4/7 | moderately | 8:29 PM | NW | 8:34 PM | E/NE |

| 4/7 | moderately | 10:05 PM | NW | 10:07 PM | NW |

| 4/8 | extremely | 9:13 PM | NW | 9:16 PM | NE |

| 4/9 | very | 8:20 PM | NW | 8:26 PM | E/NE |

| 4/9 | very | 9:56 PM | W/NW | 9:59 PM | W/NW |

| 4/10 | extremely | 9:04 PM | NW | 9:08 PM | E |

| 4/11 | extremely | 8:11 PM | NW | 8:18 PM | E |

| 4/11 | very | 9:48 PM | W/NW | 9:50 PM | W/SW |

| 4/12 | extremely | 8:55 PM | W/NW | 9:00 PM | SE |

| 4/13 | moderately | 9:40 PM | W | 9:43 PM | SW |

| 4/14 | very | 8:47 PM | W/NW | 8:52 PM | S/SE |

| 4/16 | somewhat | 8:39 PM | W/SW | 8:42 PM | S/SW |

Predictions courtesy of heavens-above.com. Times later in the month are subject to change – for the most accurate weekly predictions, check spotthestation.nasa.gov.

Meteor Showers: Lyrids active April 18 to 25, peaking on April 22

Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through the debris field of a comet or asteroid. As these objects approach the warming sun in their long orbits, they leave tiny bits behind – imagine pebbles popping out the back of a large gravel truck on an increasingly bumpy road. In the case of meteor showers, the brilliant streaks you see are due to particles usually no larger than grains of sand. The Earth plows through the swarm of these tiny particles at up-to 12 miles-per-second. High in the upper atmosphere, these particles burn up due to friction and ionize the air around them, producing the long light trails we see. We can predict the peak observing nights for a meteor shower because we know when and where in Earth's orbit we'll pass through the same part of the Solar System – this yearly periodicity in meteor activity is what let us identify and name meteor showers well before we ever had evidence of what caused them.

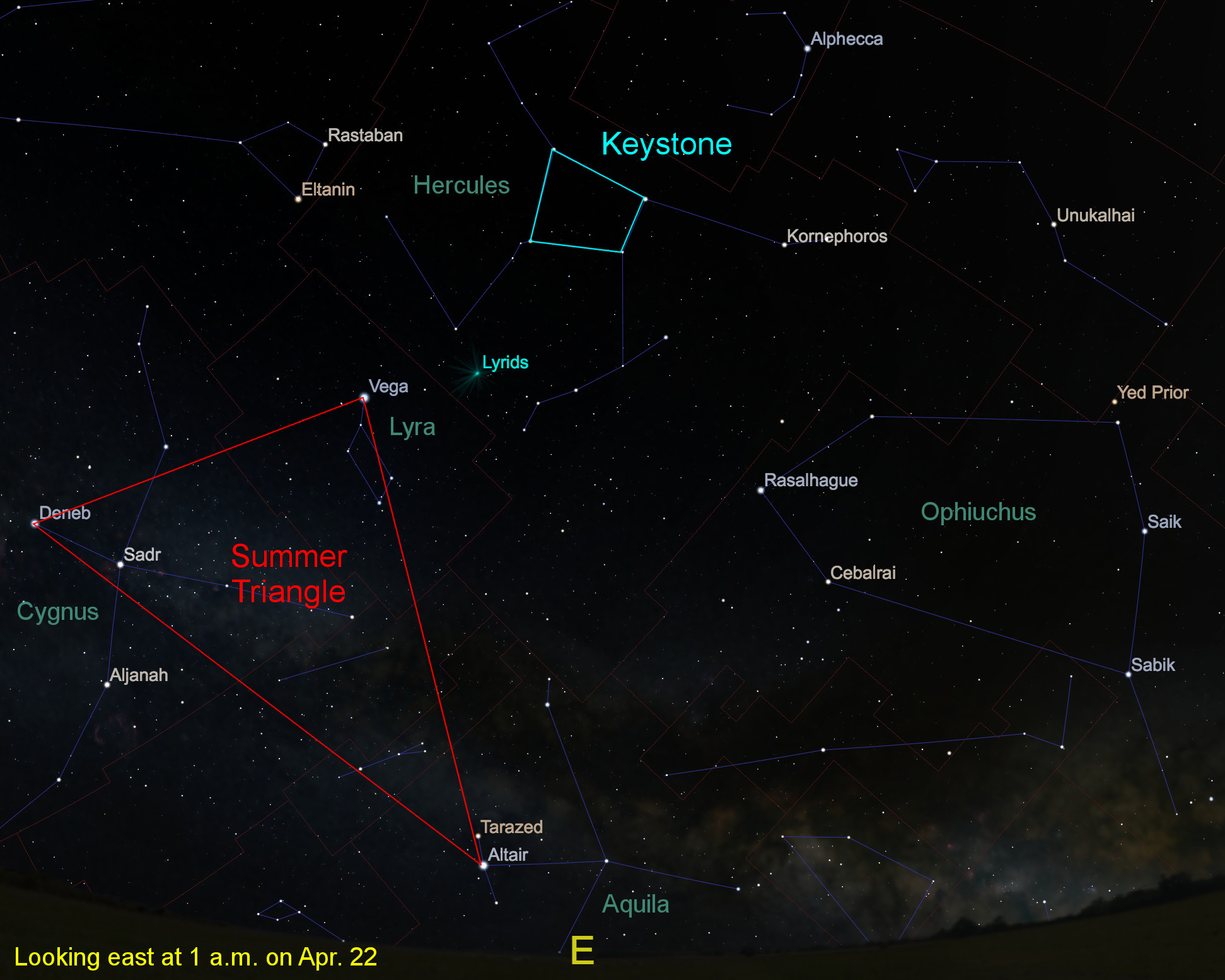

The name of each meteor shower is based on the constellation from which the shooting stars appear to radiate – a position in the sky we call the radiant. The radiant for the Lyrids is precariously close to the funny bone of the troubled Hercules, but still considered within the official borders of Lyra the Harp. Finding the radiant is as easy as finding the bright star Vega, which rises to the northeast just before 9:00 p.m. on the active nights of the Lyrids. Those staying awake until 1:00 a.m. are treated to the complete Summer Triangle – an asterism discussed in several previous articles and a reminder that the summer constellations are well on their way.

How to observe: The Lyrids peak in the presence of a sliver of a waning crescent Moon. This is excellent news for observers annoyed by the many washed-out 2016 meteor showers, as the Moon will not be bright enough to dull bright Lyrid trails. One thing you'll be sure *not* to see this year is the comet producing the Lyrids – Comet Thatcher (C/1861 G1) has a 415-year orbit as was last in our part of the Solar System in 1861, just a bit too early for anyone to even attempt capturing it on a photographic plate. Instead of spying Thatcher, consider trying to catch the wispy nebulosity of Comet 41P/Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresak, which should be bright enough to see under dark skies with good binoculars. To find it on the 22nd, place the eastern two stars of the head of Draco, known as "the lozenge," in your binocular field of view – Comet 41P/TGK should lie just towards the center.

To optimize your Lyrid experience, lie flat on the ground with your feet pointed towards Lyra and your head elevated – meteors will then appear to fly right over and around you. Counts and brightness tend to increase the later you stay out, with peak observing times usually between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m.

Learn a constellation: Ursa Minor

Ursa Minor, the "Little Bear," is neither large or bright. Its close proximity and resemblance to fellow kitchen-aid the Big Dipper has earned it the appropriate nickname the "Little Dipper." While three of its stars are easy to pick out under most skies, seeing all seven stars in the constellation requires fairly dark skies. Fortunately, the tip of the handle and the back two stars of the bowl are the brightest three, helping you to frame out your search for the other four. Finding Polaris is made easier by the Big Dipper – drawing a straight line from the edge bowl stars of the Big Dipper and away from the open face of the bowl will lead you to a star that is not particularly bright, but is a stand-out because there are so very few prominent stars in its vicinity.

Much of the extra attention paid to Ursa Minor is due to Polaris, the "North Star." At present, Earth's rotation axis is pointed very close to this star. That is to say, if you stared at this star all night long, you'd see it stay put while everything else seemed to spin around it. Patient observers with clear skies can even point their cameras at Polaris, walk away with the shutter open for several hours, and produce images of long star trails. Stars closest to Polaris leave the shortest trails, while stars further south get stretched out into longer and longer arcs.

Polaris is actually a busy system on its own – it is a triple star system, with a massive yellow-white supergiant at its center and two companion yellow-white stars around it. Polaris is also what is known as a Cepheid variable star – the brightest in our nighttime sky. Its brightness varies periodically by a small amount every 4 days. The bowl of the Little Dipper will just barely fit within the field of view of 10×50 binoculars. The bright bowl star Kochab is an orange giant featuring at least one exoplanet – a gas giant six times more massive than Jupiter that orbits in 522 days. Its neighbor Pherkad has what appears to be a small companion star, similar to what one sees with the stars Mizar and Alcor in the handle of the Big Dipper. In the case of Pherkad, this pair is what we refer to as an "optical binary," meaning they appear close together as we look in the sky, but the dimmer Pherkad companion is actually almost 100 light years closer to us than Pherkad.

Dr. Damian Allis is the director of CNY Observers and a NASA Solar System Ambassador. If you know of any other NY astronomy events or clubs to promote, please contact the author.

Original Posts:

- https://www.newyorkupstate.com/outdoors/2017/03/upstate_ny_stargazing_in_april_comet_hunting_and_the_lyrid_meteor_shower.html

- https://www.syracuse.com/outdoors/2017/03/upstate_ny_stargazing_in_april_comet_hunting_and_the_lyrid_meteor_shower.html

Tags: