Author's Note: The "Upstate New York Stargazing" series ran on the newyorkupstate.com and syracuse.com websites (and limited use in-print) from 2016 to 2018. For the full list of articles, see the Upstate New York Stargazing page.

November Stargazing in Upstate NY: Catch the sometimes roaring Leonids

Updated: Mar. 22, 2019, 12:53 a.m. | Published: Oct. 31, 2016, 3:13 p.m.

(Special to Syracuse.com)

By Damian Allis | Contributing writer

There are some at observing sessions who, upon seeing a satellite for the first time, marvel at just how bright something so small and far away can be. There are several individual high-fliers and families of orbiting objects, and you can use such websites as heavens-above.com, n2yo.com, and spaceweather.com/flybys/ to predict their paths with great accuracy. You need not do your homework, however. Anyone with decent night vision will see satellites jump out against the backdrop of stationary stars all night long, moving swiftly until they set below the horizon, enter Earth's shadow, or reorient their solar panels.

With a sturdy tripod and a camera that can do long exposures – and we're only talking 15 seconds or more – you can catch the trails of bright satellites from urban locations. If your timing is right, you might even try for a combination satellite/airplane flyover. With a long exposure, the satellite will produce a long, continuous light trail, while the flashing lights of the airplane will produce a bright dotted line.

The image above is one such example of a well-placed International Space Station (ISS) flyover, complete with the bright stars of the most famous asterism in the Northern Hemisphere – The Big Dipper. Thanks to the long exposure, it is even possible to see that some of the stars are slightly red-orange and not just pure white pinpoints of light. Thanks to some straightforward physics, we know that our photographer opened his shutter at 7:49:57 p.m. and closed it at 7:50:27 p.m., and we could have figured out the exact day and time from the recent orbits of the ISS even if we didn't know that the picture was taken on Oct. 12.

Your First Steps Outside:

NOTE: Daylight Saving Time ends at 2:00 a.m. on Sunday, November 6th. Because of this, reported times for some month-long events listed below will be one hour earlier starting on the Nov. 6. To account for this difference, certain reported times below are in a [before the 6th]/[after the 6th] format, while other times correctly account for the time change.

Items and events listed below assume you're outside and observing between 8 p.m. and midnight throughout November anywhere in New York state. The longer you're outside and away from indoor or bright lights, the better your dark adaption will be. If you have to use your smartphone, find a red light app or piece of red acetate, else set your brightness as low as possible.

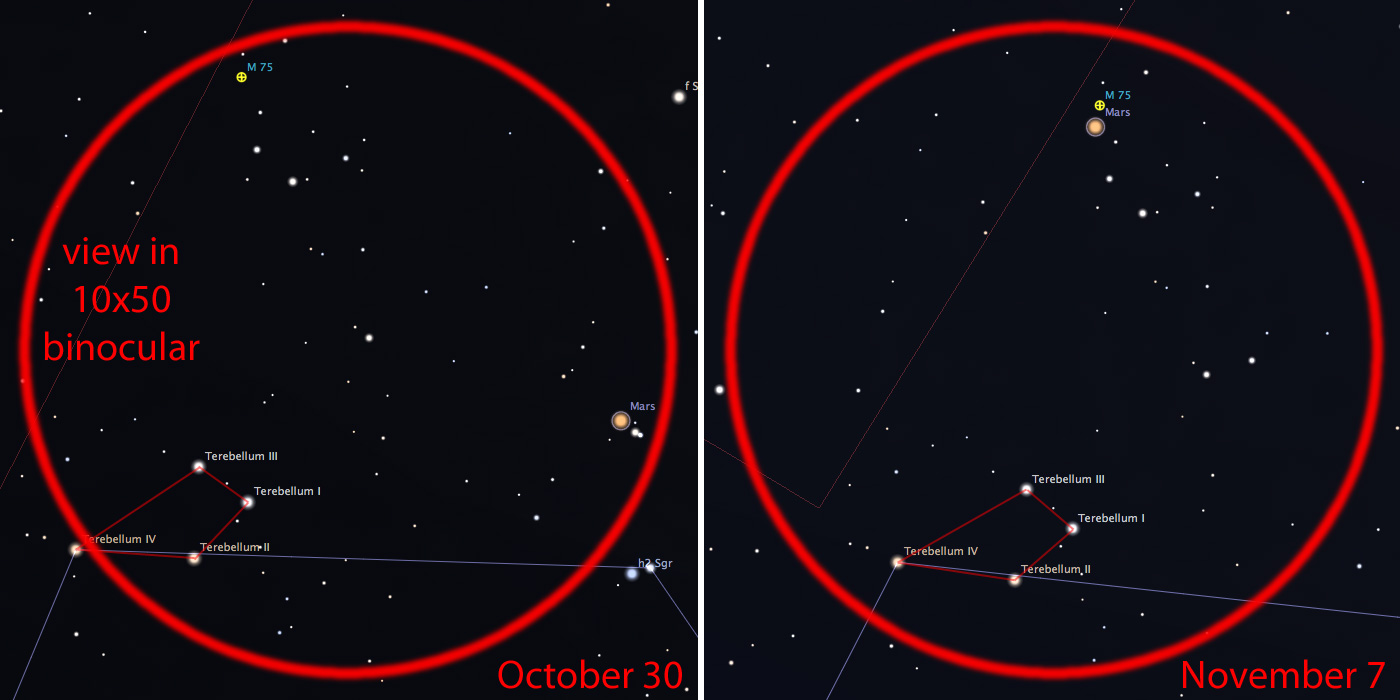

Mars: Mars will follow the horizon close to [10]/[9] p.m. all month long before setting, sliding from the southwest to the west in the process. It remains the most accessible, although not the most prominent, planet in the skies this month. Starting October 30th, Mars and the faint globular cluster M75 will be in the same field of view of a pair of 10×50 binoculars. Closest approach will occur on the night of November 7th, although the Moon that night will not make your observation of M75 easy. You can use Mars and the four stars of the tiny, ancient asterism Terebellum to help orient yourself. For a refresher on globular clusters, check out the October article.

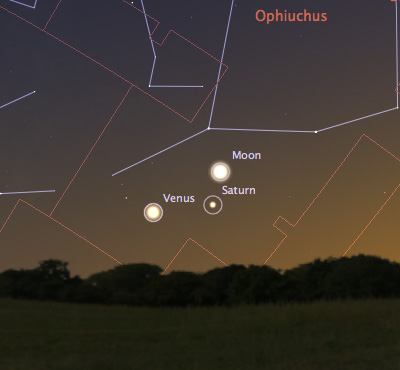

Venus: Observers unimpressed with the recent temperature change can still get some early planetary viewing in. Venus remain unmistakable to the southwest soon after sunset, making an early exit from the night sky at the beginning of the month around [7:45]/[6:45] p.m. Thanks to our relative positions in our respective orbits, we'll even be gaining about one minute of additional Venus viewing each night. By month's end, Venus will set below the SW horizon just before 7:30 p.m.

Saturn: What we gain in Venus viewing we lose in Saturn viewing. Saturn has been setting just after Venus recently, but will hit the horizon at the same time on Nov. 2, when Venus, Saturn, and the very young waxing crescent moon make for a pleasant grouping. Catch this soon after sunset, as we lose the whole group to the horizon before 7:30 p.m. Chances to catch Saturn all but end by Nov. 15, when it sets just before 6 p.m.

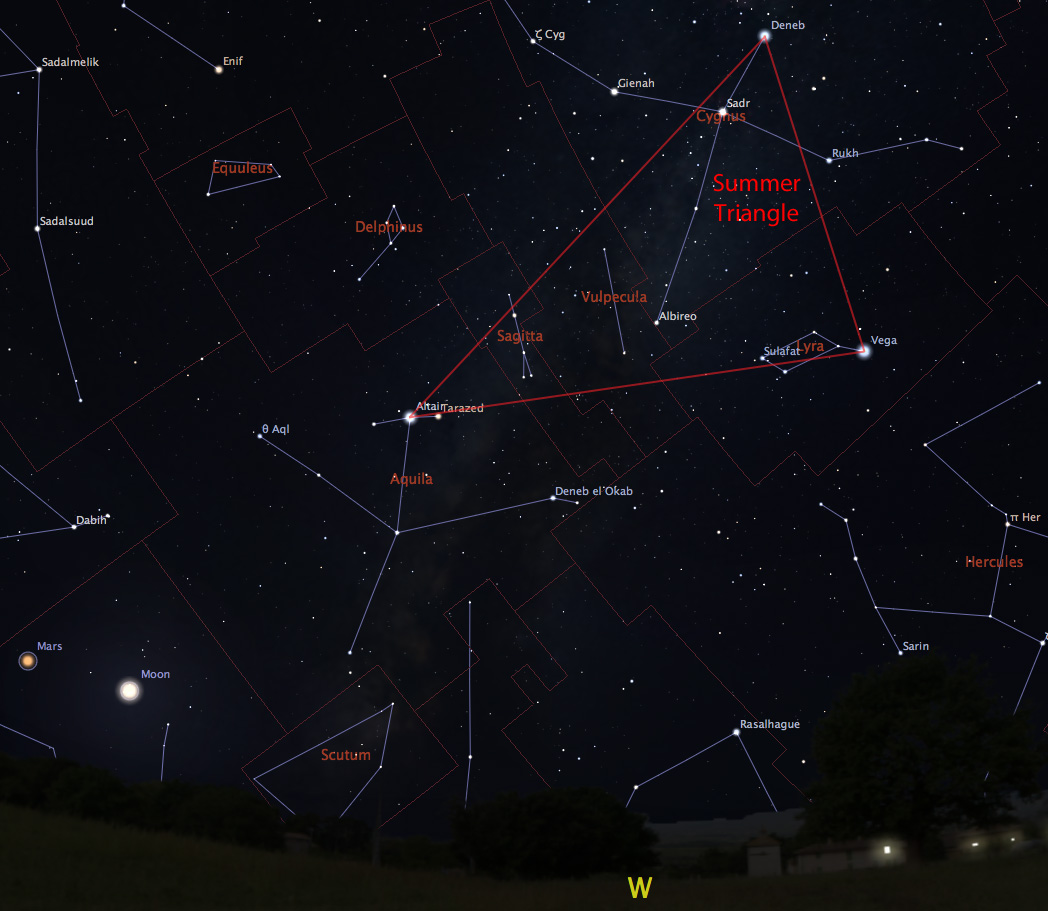

The Summer Triangle: If it was not already apparent that we're not in Summer anymore, the Summer Triangle becomes the Summer Line in pre-midnight skies this month. Our summertime southern-pointing star Altair in the constellation Aquila now sets just north of due-West earlier and earlier this month, leaving Deneb in Cygnus and the brilliant Vega in Lyra. Vega itself will drop below the horizon before midnight by mid-month, marking the transition of Cygnus the Swan into what some refer to as the Northern Cross, with Cygnus now diving head-first into the horizon to leave its wings and back-end standing upright to the west/northwest. For a refresher on the Summer Triangle, see the August and September articles in this series.

Orion, Taurus, And The Pleiades: Winter's best now make grand appearances before midnight, featuring the two closest open clusters to our Solar System. Unlike the dense globular clusters described in last month's article, open clusters contain only 10's to 100's of stars that are all gravitationally bound to one another. You can think of "open" here as referring to all of the open, dark space you can see between member stars. The Pleiades, the second-closest open star cluster to Earth, rises above the Eastern horizon after 7/6 p.m. in early November and comfortably before sunset by month's end. Following about an hour behind the Pleiades is the head of Taurus the Bull. The distinctive V-shaped head is composed of the bright red-orange star Aldebaran and "all the other" stars – this final collection of remaining notable-but-not-as-prominent stars are themselves called the Hyades and are the closest open star cluster to Earth. Contrary to some representations you might see, Aldebaran is not, in fact, a gravitationally-bound member of this cluster – it is much closer to Earth than the Hyades cluster and just happens to be placed in just the right spot to turn an otherwise less-impressive "checkmark" shape into a more distinctive "V" shape. Orion rises soon after Taurus and looks like a massive bowtie as it comes over the horizon. Only after it has fully cleared the horizon does it begin to take on the image of a human figure instead of human formal wear.

Early Riser Alert:

Jupiter: Jupiter rises above the Eastern horizon near 5:30 a.m. on Nov 1st and by 4:00 a.m. at month's end. Its four Galilean Moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – are all visible in low-power binoculars when Jupiter rises, but are washed out early by sunlight even before sunrise approaches. Jupiter and the very waning crescent moon will make a very nice pairing after 4:00 a.m. on November 25th. The next prominent change to the early morning sky will not occur until mid-February, when Saturn makes its reappearance in the sky after its November departure at sunset.

November Observing Opportunities In Upstate/Central New York:

New York has a number of evenly-spaced astronomers, astronomy clubs, and observatories that host sessions throughout the year. Many of these sessions are free and open to the public, often close to the New Moon when skies are darkest and the chance for seeing deep, distant objects is greatest. These observers and facilities are the very best places to see the month's best objects using some of the best equipment, all while having very knowledgeable observers at your side to answer questions and guide discussion. Many of these organizations also hold monthly meetings, where seasoned amateurs can learn about recent news and discoveries from guest lecturers, and brand new observers are encouraged to join and begin the path towards seasoned amateur status.

Announced public sessions from several respondent NY astronomy organizations are provided below for November. As wind and cloud cover are always factors when observing, please check the website links or email the groups for directions, to find out about any fees, and to double-check about an event the day of the announced session. Also note that some groups will include weather-alternate dates for scheduled sessions.

Astronomy Events Calendar

| Organizer | Location | Event | Date | Time | Contact Info |

| Adirondack Public Observatory | Tupper Lake | Public Star Gazing | Nov. 4 | 6:30 PM | email, website |

| Adirondack Public Observatory | Tupper Lake | Public Star Gazing | Nov. 18 | 5:30 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Octagon Barn Star Party & Lecture | Nov. 4 | 7:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Star Party at Grafton Lakes | Nov. 4 | 7:30 – 11:30 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Star Party at Landis Arboretum | Nov. 25, 26 | 8:00 – 10:00 PM | email, website |

| Baltimore Woods | Marcellus | Public Viewing With Bob Piekiel | Nov. 4/5 | 7:00 – 9:30 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | "What is inside Jupiter?" Lecture And Public Viewing | Nov. 4 | 7:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Observing @ Barnes & Noble | Nov. 5 | 6:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | "High Performance Computing" Lecture And Public Viewing | Nov. 11 | 7:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Observing @ Barnes & Noble | Nov. 12 | 6:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | "Water from Rain" Lecture And Public Viewing | Nov. 18 | 7:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Observing @ Barnes & Noble | Nov. 19 | 6:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | "Black Holes on Black Friday" Lecture And Public Viewing | Nov. 25 | 7:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Observing @ Barnes & Noble | Nov. 25 | 6:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Mohawk Valley Astronomical Society | Waterville | Public Star Gazing | Nov. 5 | 7:30 PM – 12:00 AM | email, website |

| Mohawk Valley Astronomical Society | Waterville | Public Star Gazing | Nov. 12 | 7:30 PM – 12:00 AM | email, website |

| Mohawk Valley Astronomical Society | Waterville | Public Star Gazing | Nov. 19 | 7:30 PM – 12:00 AM | email, website |

| Mohawk Valley Astronomical Society | Waterville | Public Star Gazing | Nov. 26 | 7:30 PM – 12:00 AM | email, website |

ISS And Other Bright Flyovers:

Satellite flyovers are commonplace, with several bright passes per hour, yet a thrill to new observers of all ages. Few flyovers compare in brightness or interest to the International Space Station. The flyovers of the football-sized craft with its massive solar panel arrays can be predicted to within several seconds and take several minutes to complete.

The ISS this month is going to be an excellent morning target, but will not make any appearance in the evening sky until month's end. On the bright side, December will see several bright evening passes early in the month. Simply go out a few minutes before the start time, orient yourself, and look for what will at first seem like a distant plane.

ISS fly-bys

| Date | Brightness | Approx. Start | Start Direction | Approx. End | End Direction |

| 11/1 | very | 7:08 AM | SW | 7:14 AM | E/NE |

| 11/2 | moderately | 6:16 AM | SSW | 6:21 AM | E |

| 11/3 | extremely | 6:59 AM | W/SW | 7:06 AM | NE |

| 11/4 | very | 6:08 AM | S/SW | 6:13 AM | E/NE |

| 11/5 | very | 6:51 AM | W | 6:57 AM | NE |

| 11/6 | extremely | 5:01 AM | N | 5:04 AM | NE |

| 11/7 | very | 5:44 AM | W/NW | 5:48 AM | NE |

| 11/8 | moderately | 4:53 AM | N/NE | 4:55 AM | NE |

| 11/9 | moderately | 5:36 AM | N/NW | 5:39 AM | NE |

| 11/10 | moderately | 4:45 AM | N/NE | 4:46 AM | NE |

| 11/10 | moderately | 6:18 AM | NW | 6:23 AM | NE |

| 11/11 | moderately | 5:27 AM | N/NW | 5:30 AM | NE |

| 11/12 | moderately | 6:10 AM | NW | 6:15 AM | E/NE |

| 11/13 | moderately | 5:19 AM | N | 5:22 AM | NE |

| 11/14 | moderately | 6:01 AM | NW | 6:06 AM | E |

| 11/15 | moderately | 5:10 AM | N | 5:13 AM | E/NE |

| 11/16 | very | 5:52 AM | NW | 5:58 AM | E/SE |

| 11/17 | very | 5:02 AM | NNE | 5:05 AM | E |

| 11/18 | extremely | 5:44 AM | W/NW | 5:49 AM | SE |

| 11/19 | very | 4:54 AM | E | 4:56 AM | E/SE |

| 11/19 | moderately | 6:27 AM | W | 6:31 AM | S |

| 11/20 | very | 5:36 AM | W/SW | 5:39 AM | S/SE |

| 11/21 | moderately | 4:46 AM | SE | 4:47 AM | SE |

| 11/28 | somewhat | 6:24 PM | S | 6:25 PM | S |

| 11/29 | somewhat | 7:06 PM | SW | 7:07 PM | SW |

| 11/30 | very | 6:14 PM | S/SW | 6:16 PM | S/SE |

Predictions courtesy of heavens-above.com.

Moon: Lunar Phases

| New: | First Quarter: | Full: | Third Quarter: | New: |

| Oct. 30, 1:30 PM | Nov. 7, 2:51 PM | Nov. 14, 8:52 AM | Nov. 21, 3:33 AM | Nov. 29, 7:18 AM |

The moon's increasing brightness as full moon approaches washes out fainter stars, random meteors, and other celestial objects – this is bad for most observing, but excellent for new observers, as only the brightest stars (those that mark the major constellations) and planets remain visible for your easy identification. If you've never tried it, the moon is a wonderful binocular object.

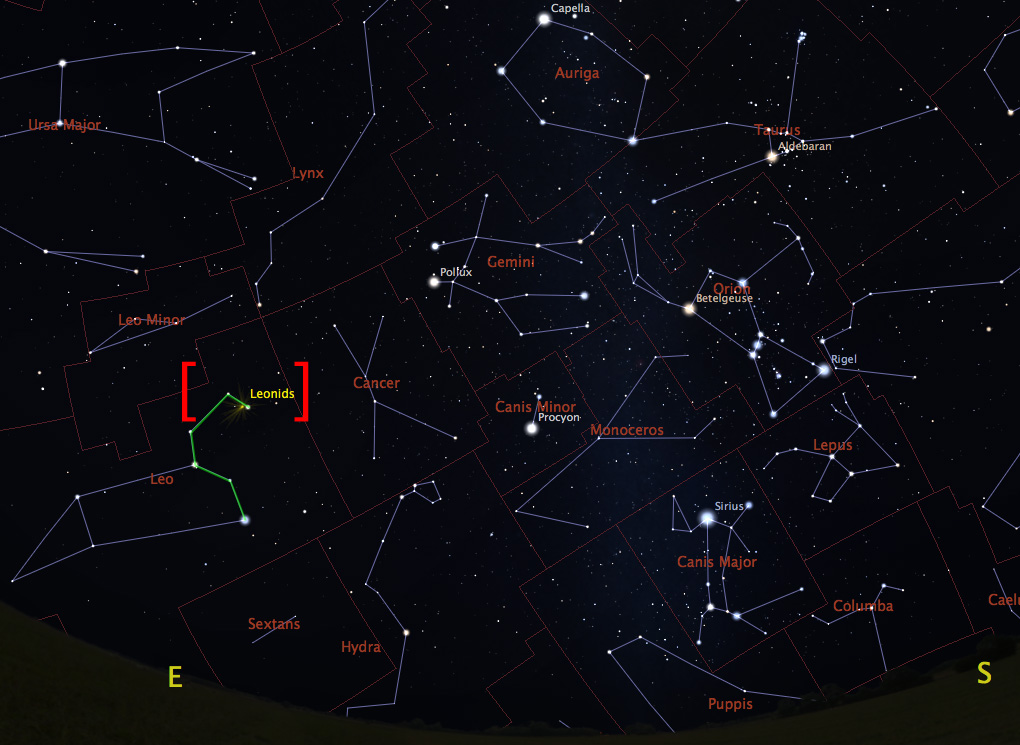

Meteor Showers: Leonids, Peaking Nov. 16-18

Meteor showers are the result of the Earth passing through the debris field of a comet or asteroid. As these objects approach the warming sun in their long orbits, they leave tiny bits behind – imagine pebbles popping out the back of a large gravel truck on an increasingly bumpy road. In the case of meteor showers, the brilliant streaks you see are due to particles no larger than grains of sand. The Earth plows through the swarm of these tiny particles at up-to 12 miles-per-second. High in the upper atmosphere, these particles burn up due to friction and ionize the air around them, producing the long light trails we see. We can predict the peak observing nights for a meteor shower because we know when and where in Earth's orbit we'll pass through the same part of the Solar System – this yearly periodicity in meteor activity is what let us identity and name meteor showers well before we ever had evidence of what caused them.

The name of each meteor shower is based on the constellation from which the shooting stars appear to radiate – a position in the sky we call the radiant. In the case of the Leonids, the meteor shower radiant appears to be just within Leo the Lion's mane, which rises from the east after midnight this month. The meteor shower itself is provided to us by Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle, whose 33-year orbit will return it to the inner solar system in 2031.

How to observe: The Leonids can be impressive and impressively bright, with up-to 15 meteors per hour expected. Sadly, the Moon will be prominent in the late-night/early-morning sky during the days around the Leonid peak, making for a far less impressive display.

Leo marks the position of the meteor shower radiant, meaning the meteors themselves will seem to shoot roughly from the east to the west. To optimize your experience, lie flat on the ground with your feet pointed east and your head elevated – meteors will then appear to fly right over and around you. Counts and brightness tend to increase the later you stay out, with peak observing times usually between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. The swarm of tiny particles is distributed broadly in orbit, meaning some people may see shooting stars associated with the Leonids during the middle and end of the month.

Learn A Constellation: Cygnus

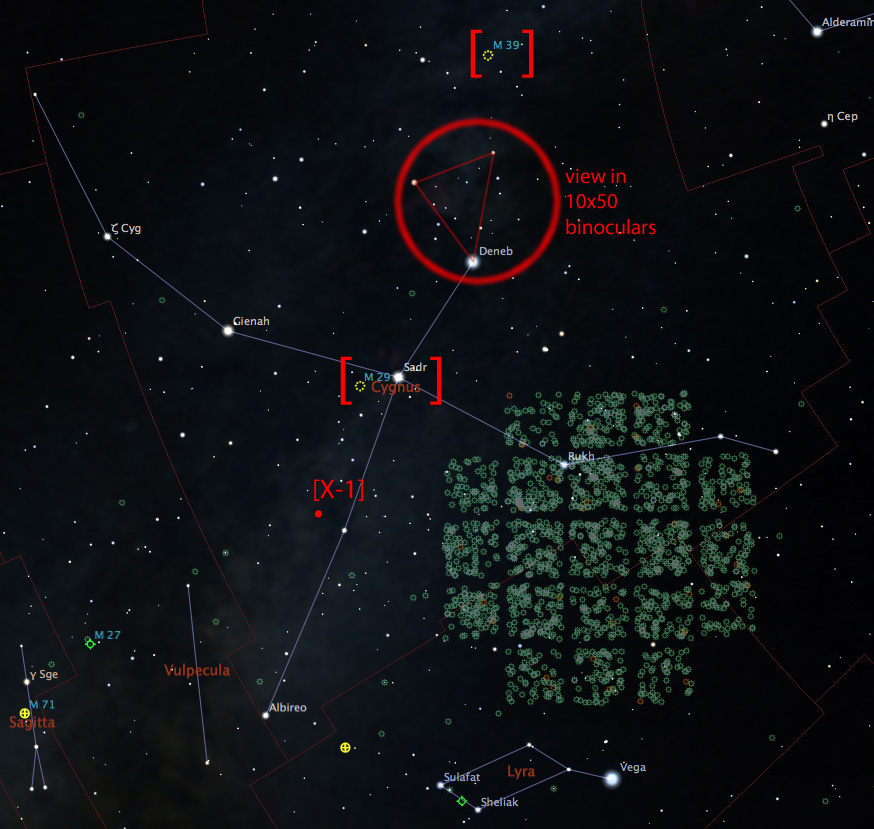

The constellation Cygnus the Swan has reared its beak in the August and September articles, as its tail star Deneb is one of the corners of the Summer Triangle. If we imagine its wings fully expanded, the body of Cygnus happens to line up very well with the plane of the galaxy. When we look at the body and long neck, we're taking a look into the thicket of the spiral arm that is our nesting place in the Milky Way.

Cygnus is a prominent constellation in a busy part of the nighttime sky – but its placement right above us during prime summer observing hours makes binocular viewing a literal pain in the neck. As mid-autumn gives way to late autumn, Cygnus reaches the western sky during more reasonable observing hours, giving us a far more comfortable opportunity to explore this part of the galaxy.

The easiest way to find Cygnus is to search for the Summer Triangle itself – which for many eyes will mean finding the bright star Vega in Lyra the Harp first. For this, simply orient your head to the west/northwest, keeping in mind that the brilliantly bright Venus to the southwest will *not* be the star you're looking for in the early evening. With Vega and Lyra found, the distinctive cross shape should jump out at you to Vega's upper left. Deneb will be the bright east-pointing tip, followed by Sadr at the crossroads. Glenah and Rukh make up the joint in the wings, while Albireo marks the swan's head. Albireo is itself a pleasant big bino/telescope object, as it splits into two stars upon sufficient magnification, with one a pronounced red/orange and the other giving off a slight blue twinge to most eyes.

For significant deep sky objects, we continue with the open cluster theme begun with the Hyades and Pleiades in Taurus the Bull. M29 is a small open cluster just to the left of Sadr – a dim object requiring magnification and eagle eyes to really take in. The open cluster M39 lies above Deneb. With Deneb in your sights, identify a bright triangle taking up much of the field of view of your binoculars. Use the star farthest from Deneb as an anchor to slide the binos up to search for a small grouping of dim stars.

Those with a keen imagination are welcome to take a gander just to the south of the star half-way between Sadr and Albireo. You won't be able to see it, but marked in the image above is the location of the first X-ray source ever classified as a black hole – the existence of which made for a long-running game of gravitational chicken between famed physicists Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne. These two and other astrophysicists, as well as most progressive rock fans, know this object as Cygnus X-1.

Beyond M29, M39, a black hole, and its prime position along the Milky Way, you can add one more feather to the cap of Cygnus. The green squares in the image above mark the location where the NASA Kepler Mission undertook a multi-year survey for extrasolar planets, finding (so far) over 2,300 of the 3,200 confirmed extrasolar planets in our Milky Way – a search for which astronomers are just getting started. When you look to the northern wing of Cygnus, consider how many exoplanets this telescopic fox captured in only nearby stars, then consider how small a patch of the night sky this galactic hen house represents.

Dr. Damian Allis is the director of CNY Observers and a NASA Solar System Ambassador. If you know of any other NY astronomy events or clubs to promote, please contact the author.

Original Posts:

- https://www.newyorkupstate.com/outdoors/2016/10/november_stargazing_in_upstate_ny_catch_the_sometimes_roaring_leonids.html

- https://www.syracuse.com/outdoors/2016/10/november_stargazing_in_upstate_ny_catch_the_sometimes_roaring_leonids.html

Tags: