Author's Note: The "Upstate New York Stargazing" series ran on the newyorkupstate.com and syracuse.com websites (and limited use in-print) from 2016 to 2018. For the full list of articles, see the Upstate New York Stargazing page.

Upstate NY Stargazing In March: Messier Marathon and the Lunar Occultation of Aldebaran

Updated: Feb. 28, 2017, 5:12 p.m. | Published: Feb. 28, 2017, 4:12 p.m.

By Damian Allis | Contributing writer

When someone refers to an astronomical object as "M" and a number, just what do they mean?

Once upon a time in astronomy, we didn't much know anything. Our classification throughout most of human history divided the nighttime sky into (1) pinpoints of light that didn't move with respect to each other (stars), (2) points of light that did move (planets), (3) random streaks of light that moved very quickly and disappeared (meteors), (4) the very rare pinpoints of light that grew bright and then disappeared completely (nova, supernova) and (5) the Moon.

There was also a rare sixth kind of object – comets. Comets grew bright over time before disappearing again, moved with respect to the backdrop of stars, looked like a hazy ball of light instead of a sharp pinpoint, and some were even known to come back around our way every certain number of years – a true hybrid of properties. Perhaps the most famous comet is the 75-ish year period Halley's Comet. Literary buffs will know that Mark Twain was born in 1835, the year of a Halley fly-by, and died in 1909, the year of the next Halley pass. He was even quoted as saying "It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet."

European history buffs may know that the 1066 fly-by of Halley's Comet was seen as an omen – albeit an eventually poor one for Harold II of England, who suffered death and defeat at the swords and stirrups of William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings. The Bayeux Tapestry, which records the events leading up to this famed battle, even includes the sighting of the at-that-time-unnamed Halley's Comet.

Now we zoom in on the "M" – as it happens, many deep sky objects, including globular star clusters, galaxies, and nebulae, can look a bit comet-ish when magnified. This is especially true in poor quality equipment, where bad optics make everything unresolvable, adding a hazy glow to further confuse the issue. The "street cred" that came with the discovery of and naming rights for comets instigated many to push the limits of scope building and observing after Galileo's first foray into telescope observing, as better optics and higher magnification meant catching sight sooner than anyone else. Fortunately for methodical comet hunters, many of the hazy deep sky objects in their sights did not move in the sky with respect to the stars around them – meaning, to borrow from another space adventure, "these aren't the comets you're looking for."

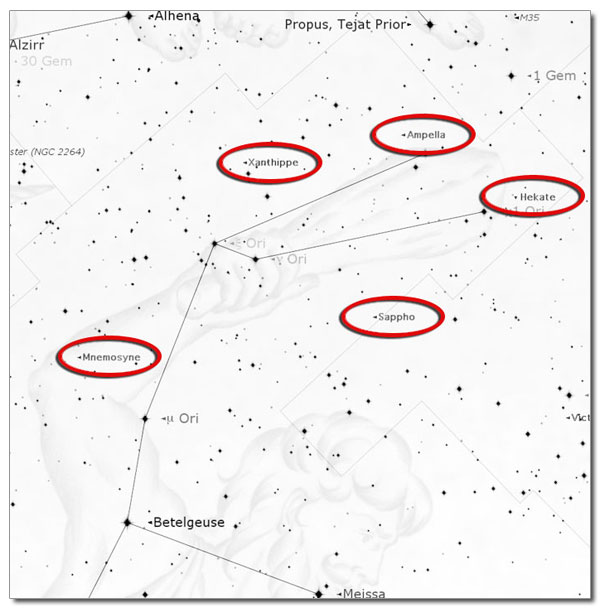

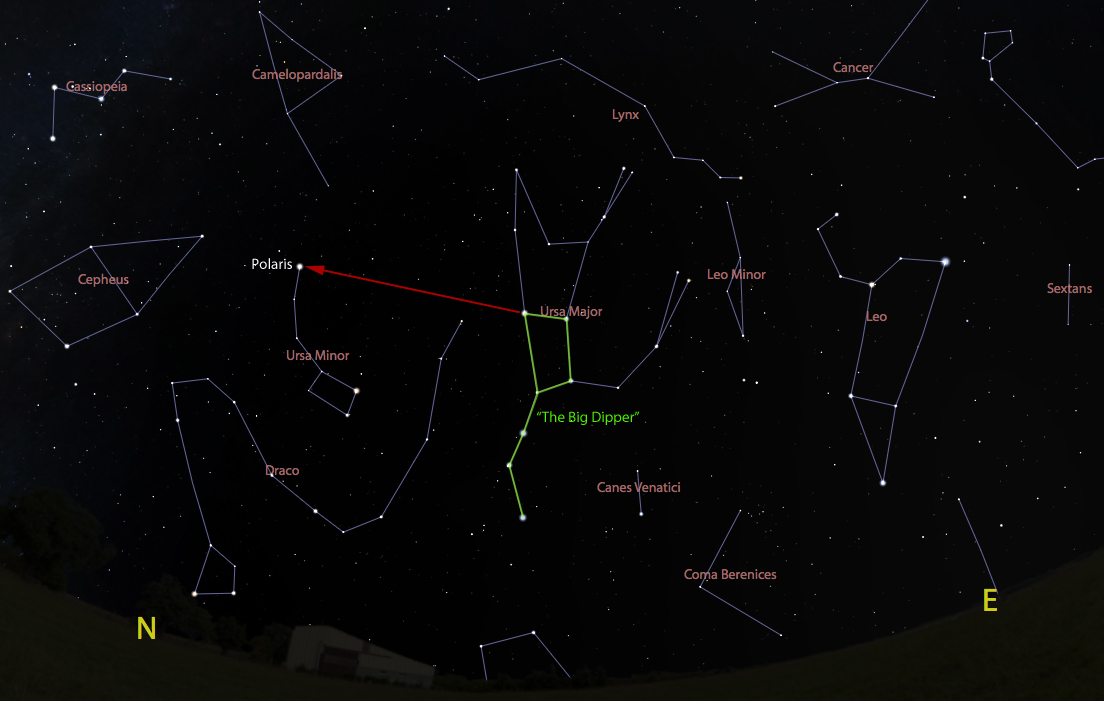

Enter the "M" – Charles Messier, the famed French comet hunter whose observing prowess gave him a near-monopoly on comet discoveries between 1760 and 1785. In an effort to keep track of stationary stellar fuzz balls, and to pre-empt the erroneous reporting of new comets by others, Messier marked the locations of 17 comet-like objects in the sky that did not move, added 28 other fixed objects discovered previously, and published all 45 in 1774 in what became the first Messier Catalogue. The final catalogue published by Messier and his assistant Pierre Mechain in 1781 included 103 objects. The list was further expanded to 110 by later astronomers who saw evidence for the observations of M104 to M110 in M+M's observing logs, with M110 added just in 1967. The Messier Catalogue accounts for nearly all of the deep sky objects you can see with a decent pair of binoculars in the Northern Hemisphere.

For those keeping track, the irony of the whole situation is that Messier, famed comet hunter, is remembered for making a catalogue of those things which are, in fact, not comets.

The entire Messier Catalogue, spread throughout the sky as it is, can be observed in its entirety under clear, dark skies very near the New Moon between mid-March and early April. Amateur astronomers the world over engage in what is known as the "Messier Marathon," one of the great yearly tests of an observer's equipment, eyesight, and patience. You have to start *very* soon after sunset to catch the earliest setters, then can enjoy a more leisurely tour of the nighttime sky, sneaking in an occasional nap or big cup of coffee before catching the last few objects *very* soon before sunrise. These marathons are not easy! Observers with several years of experience may have trouble seeing the dimmest members of the list, but even new observers with good binoculars and simple star charts can find the brightest members of the catalogue in what are often called "Messier Sprints." A web search for "Messier Marathon" will provide numerous useful links, including maps to these objects, recording logs for each object, and even the most efficient search order to find and record your observations.

March lectures and observing opportunities

New York has a number of evenly-spaced astronomers, astronomy clubs, and observatories that host public sessions throughout the year. Many of these sessions are close to the New Moon, when skies are darkest and the chances for seeing deep, distant objects are best. These observers and facilities are the very best places to see the month's best objects using some of the best equipment, all while having very knowledgeable observers at your side to answer questions and guide discussion. Many of these organizations also hold monthly meetings, where seasoned amateurs can learn about recent discoveries from guest lecturers, and brand new observers are encouraged to join and begin the path towards seasoned amateur status.

Announced public sessions from several respondent NY astronomy organizations are provided below for March. As wind and cloud cover are always factors when observing, please check the provided contact information and/or email the groups a day-or-so before an announced session. Also use the contact info for directions and to check on any applicable event or parking fees, Some groups will schedule weather-alternate dates for some sessions.

Astronomy Events Calendar

| Organizer | Location | Event | Date | Time | Contact Info |

| Adirondack Public Observatory | Tupper Lake | Public Star Gazing | Mar. 3 | 6:00 PM | email, website |

| Adirondack Public Observatory | Tupper Lake | Public Star Gazing | Mar. 17 | 6:00 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Senior Science Day | Mar. 6 | 3:00 – 4:00 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | AAAA Meetings | Mar. 16 | 7:30 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Albany Area Amateur Astronomers & Dudley Observatory | Schenectady | Night Sky Adventure | Mar. 21 | 7:00 – 8:30 PM | email, website |

| Astronomy Section, Rochester Academy of Science | Rochester | ASRAS Meeting And Lecture | Mar. 3 | 7:30 – 9:30 PM | email, website |

| Astronomy Section, Rochester Academy of Science | Rochester | Telescope Tune-Up @ Strasenburgh | Mar. 18 | 11:00 AM – 4:00 PM | email, website |

| Baltimore Woods | Marcellus | Goodbye To Winter Skies | Mar. 3 | 7:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Baltimore Woods | Marcellus | Mercury, Jupiter, Spring Skies | Mar. 31 | 6:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Monthly Meeting | Mar. 1 | 7:00 – 9:00 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Observing | Mar. 3 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Observing | Mar. 10 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Observing | Mar. 17 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Observing | Mar. 24 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Kopernik Observatory & Science Center | Vestal | Friday Night Observing | Mar. 31 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

| Mohawk Valley Astronomical Society | Waterville | Lecture: Math And The Universe | Mar. 8 | 7:30 PM | email, website |

For those still smitten with the NASA discovery of seven Earth-sized planets around TRAPPIST-1, attendees in the Cazenovia area are invited to the free lecture "Distant Worlds: What We Know About Extra-Solar Planets And Their Potential For Habitability" on March 1st in Hubbard Hall at Cazenovia College, given by Dr. Leslie Hebb from Hobart and William Smith Colleges and co-sponsored by the Cazenovia College Science Cafe Committee and CNY Observers. For additional information, please send an email to lecture@cnyo.org.

Lunar Phases

| New: | First Quarter: | Full: | Third Quarter: | New: |

| Feb. 26, 9:58 AM | Mar. 5, 6:32 AM | Mar. 12, 10:53 AM | Mar. 20, 11:58 AM | Mar. 27, 10:57 PM |

The Moon's increasing brightness as Full Moon approaches washes out fainter stars, random meteors, and other celestial objects – this is bad for most observing, but excellent for new observers, as only the brightest stars (those that mark the major constellations) and planets remain visible for your easy identification. If you've never tried it, the Moon is a wonderful binocular object.

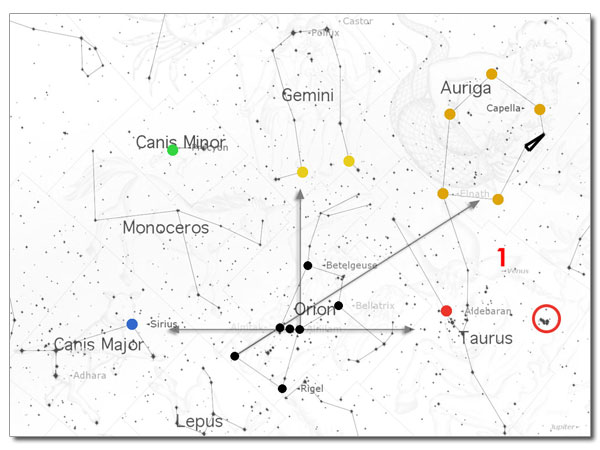

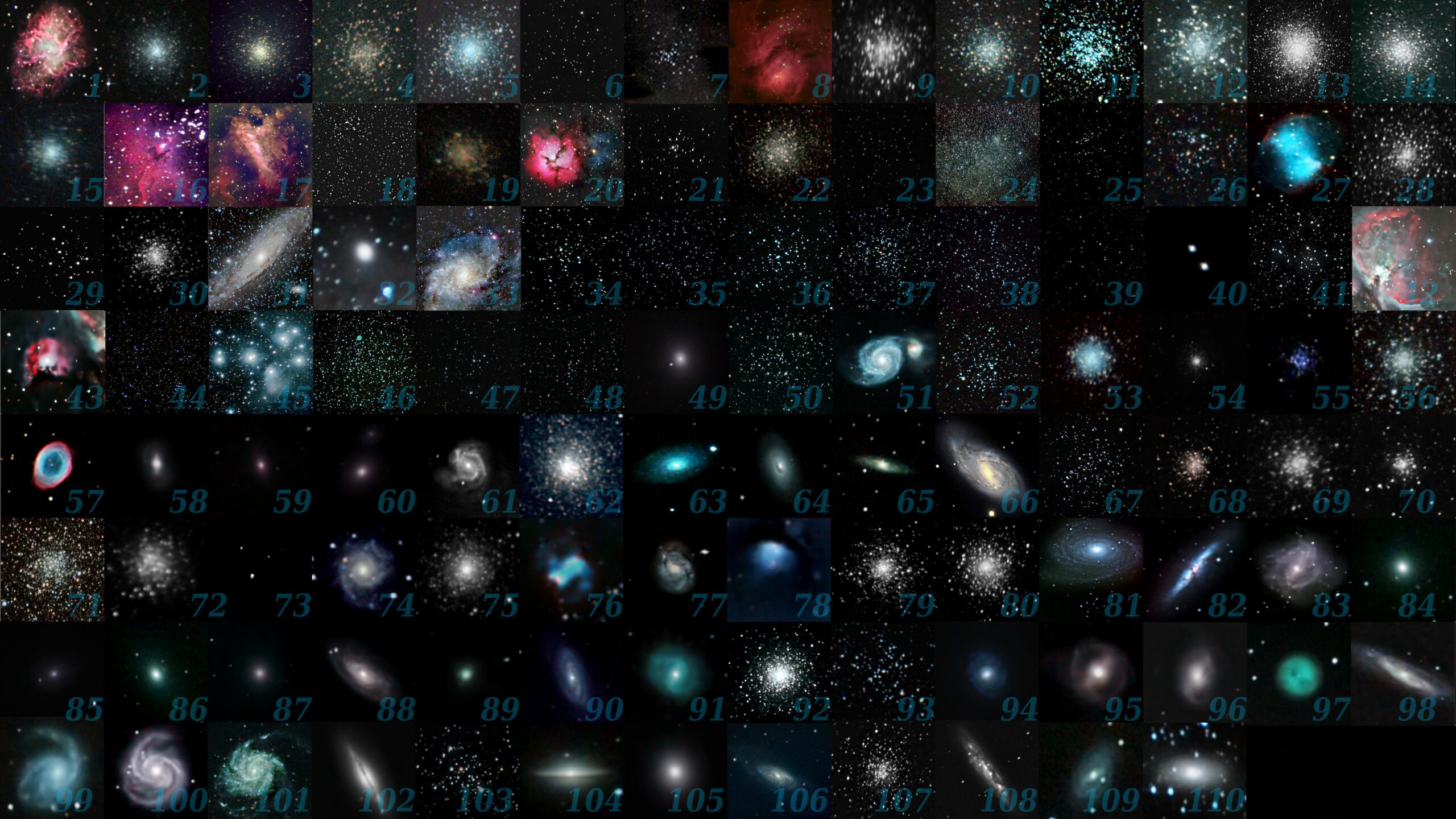

Observers throughout Central and Southern New York are in for an observational treat on the evening of March 4th, when the Moon will occult the bright star Aldebaran, bright eye of the constellation Taurus the Bull. While the Moon occults, or blocks the light from, various stars and occasional planets all the time, the Aldebaran occultation is noteworthy because many observers will see Aldebaran just graze the Moon's edge. The luckiest observers may even see Aldebaran blink several times over the course of the occultation – this is huge! With no atmosphere to speak of, the blinking of Aldebaran you might see is, in fact, the star slipping behind large lunar geological features, such as high hills and the walls of impact craters. With enough observers and enough recorded data, astronomers can even make an elevation map of the grazed region of the Moon.

For those interested in all of the details, including the best ways to observe the event and how you can record data yourself for submission to the International Occultation Timing Association (IOTA), check out their official website.

Evening And Nighttime Guide

Items and events listed below assume you're outside and observing most anywhere in New York state. The longer you're outside and away from indoor or bright lights, the better your dark adaption will be. If you have to use your smartphone, find a red light app or piece of red acetate, else set your brightness as low as possible.

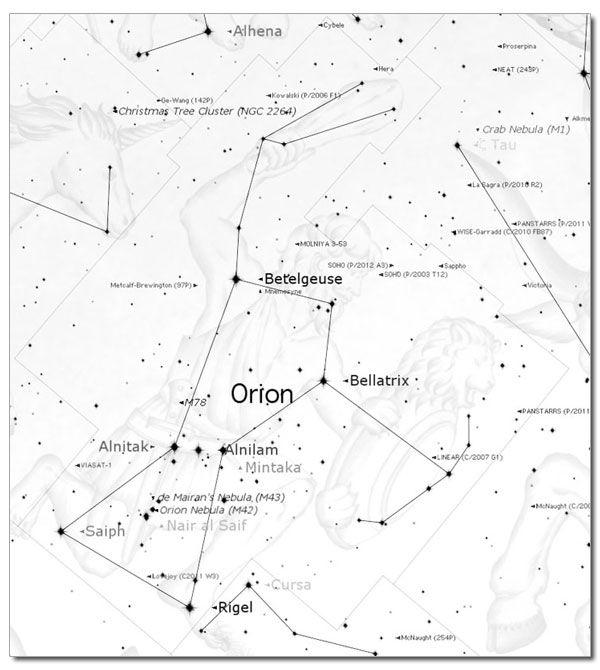

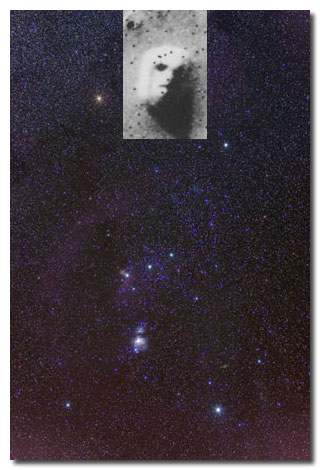

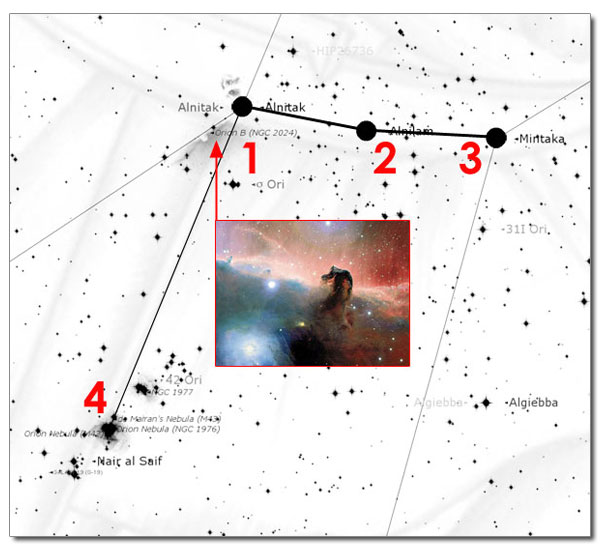

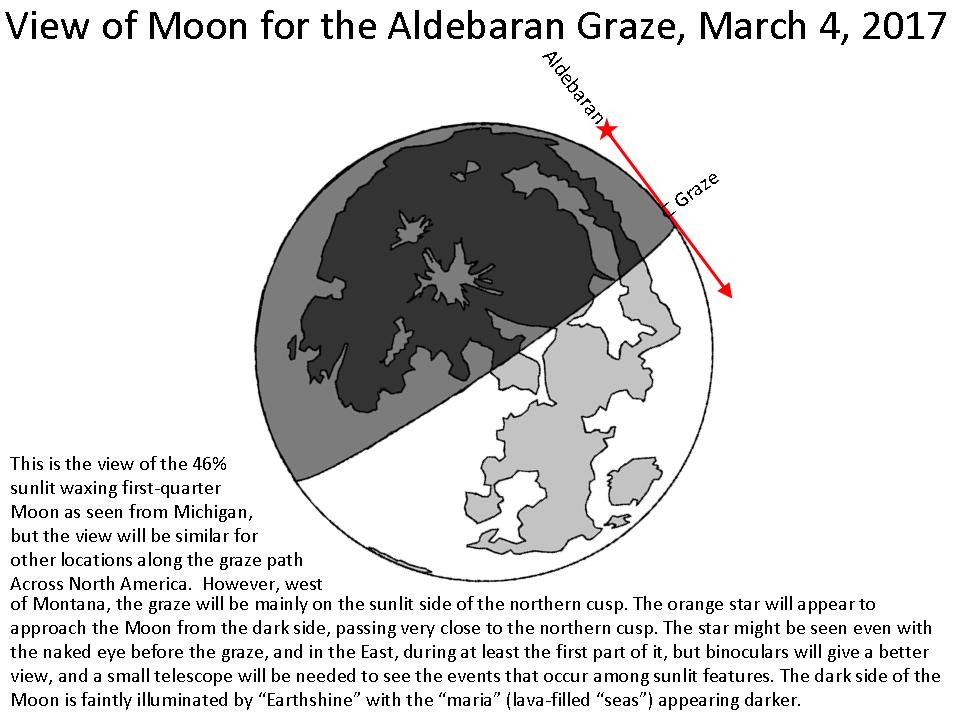

Southern Sights: Orion, Taurus, and Canis Major are now primed for nighttime observing. High above them lies the twins Gemini – two very bright stars above Betelgeuse, the bright shoulder of Orion, will help orient you to find the stars that make up their bodies. These real beauties of winter skies will be nearly gone by the end of April, after which observers will have to wake up very early in August to see them again.

Northern Sights: Observers out during the late-evening hours are treated to a prominent Big Dipper standing upright in the northeastern sky and a prominent "E" shape in the northwest – the constellation Cassiopeia. The ancient king Cepheus sits near the horizon before midnight, looking like a dilapidated old barn. Once you've found the Big Dipper, take the two stars at the end of the bowl and guide your way to a moderately bright star surrounded by a mostly empty, dark piece of sky – this is the north star and tip of the Little Dipper handle, Polaris.

Planetary Viewing

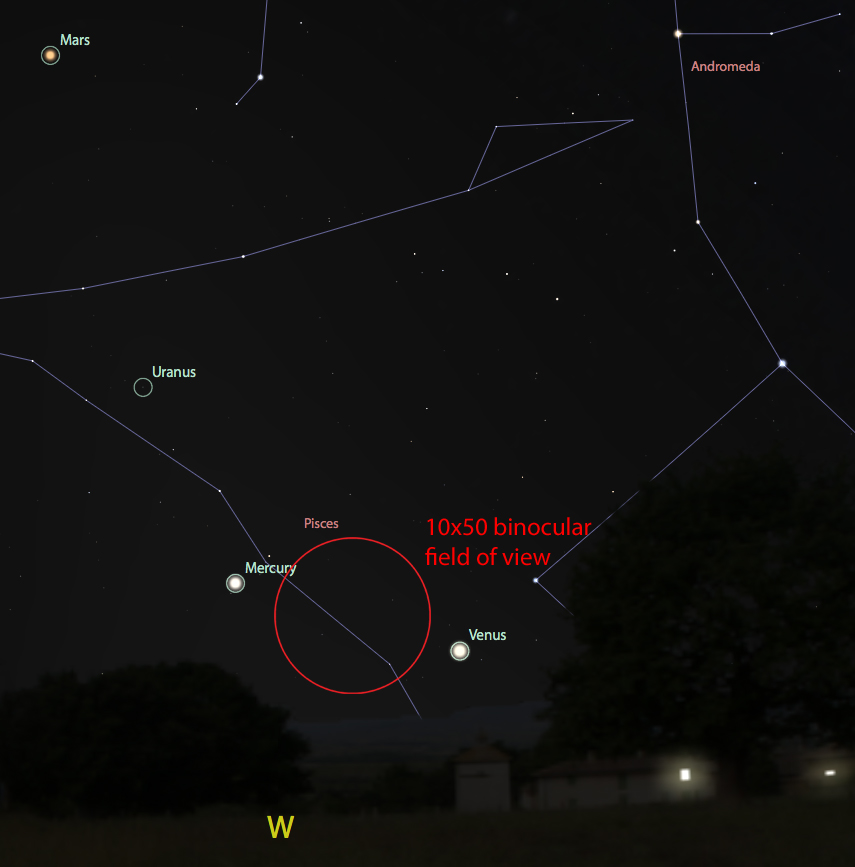

Mercury: Mercury will be a bright pinpoint of light that will appear and then set just after sunset on March 11th. For the rest of the month, Mercury rises higher and sets later each night, falling behind Venus on the 20th and rising still higher in the sky through the end of March and early April. The 20th also offers a perfect time to catch four planets – Mars, Uranus, Mercury, and Venus – in the same part of the sky. On March 31, Mercury sets just after 9 p.m. EDT after crossing the Pisces-Aries border.

Venus: Everyone's favorite misidentified UFO is going to zip along rather quickly from our view and through Pisces this month. Venus will set close to 8:30 p.m. on March 1st, a good 40 minutes or more before the crescent Moon and Mars do. On March 19th, Venus will set just after Mercury, newly arrived to the early-evening skies. On March 25th, Venus will set with the Sun and won't return to our evening skies until January of 2018. That said, Venus goes from being a bright evening object to a bright morning object instead! Between the 23rd and 25th, you have a decent chance of seeing Venus at sunset and at sunrise, after which Venus increasingly becomes a pre-dawn observing target until well into December of this year.

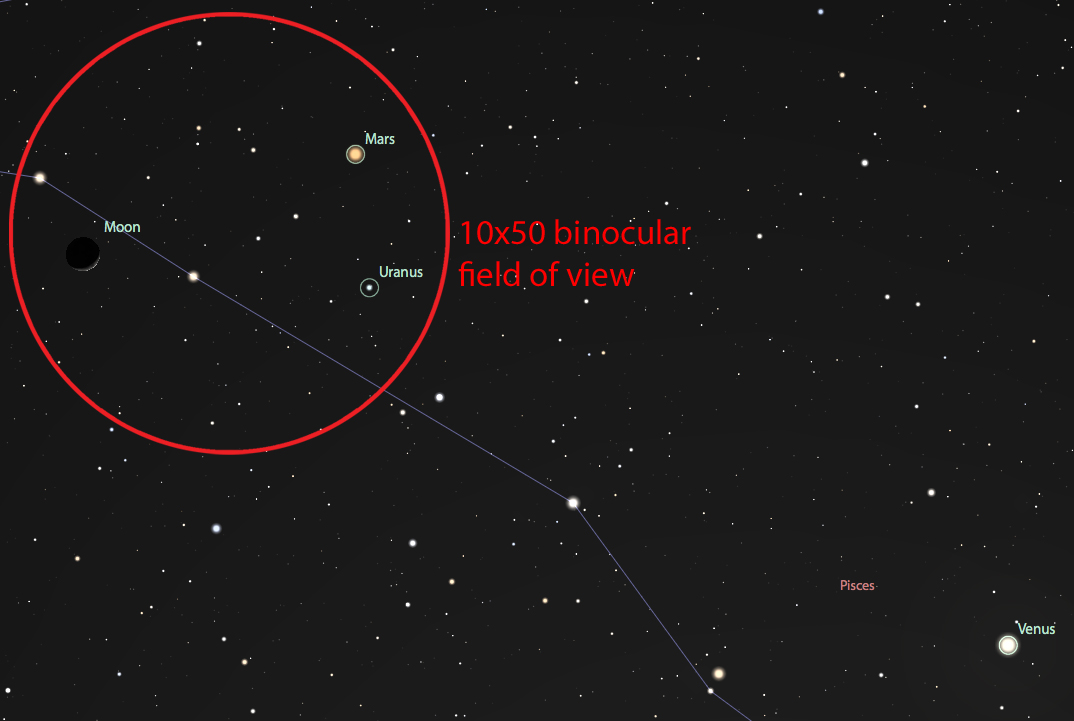

Mars: Mars will pair with the Moon this month in Pisces on March 1st and, once again, these two objects can guide you to finding the second-farthest planet in the Solar System. With luck and decent magnification, Uranus will appear as a green/blue point of light below Mars. If the Moon is too bright for easy scanning, simply wait until after the 1st for the Moon to make a little distance from Mars before trying for Uranus again. Mars will set very close to 9:20 p.m. EST / 10:20 EDT the entire month thanks to our mutual motions around the Sun, crossing the border from Pisces to Aries on March 8.

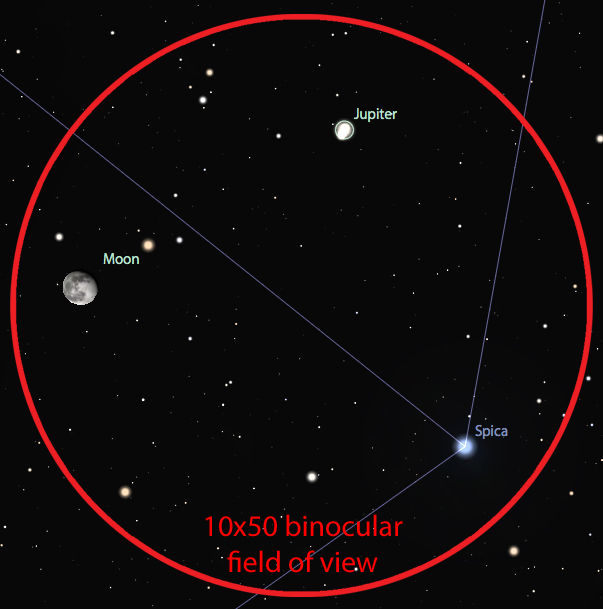

Jupiter: March marks the triumphant return of Jupiter to our late-evening and early nighttime skies. On March 1, Jupiter rises in Virgo just after 9:30 p.m. By March 31, Jupiter will just hit the eastern tree line around 8:30 p.m. EDT. Low power binoculars are excellent for spying the four bright Galilean moons – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – and you are welcome to reproduce Galileo's observations of their motions around Jupiter. In fact, your generic, big-box store binoculars are a significant improvement over the equipment Galileo had at his disposal when he first began observing the heavens, so your task is all the easier. Several online guides will even map their orbits for you so you can identify their motions nightly or, for the patient observer, even hourly. The near-full Moon and Jupiter will make for a bright grouping with the bright Virgo star Spica in 10×50 binoculars after 10 p.m. EDT on March 14.

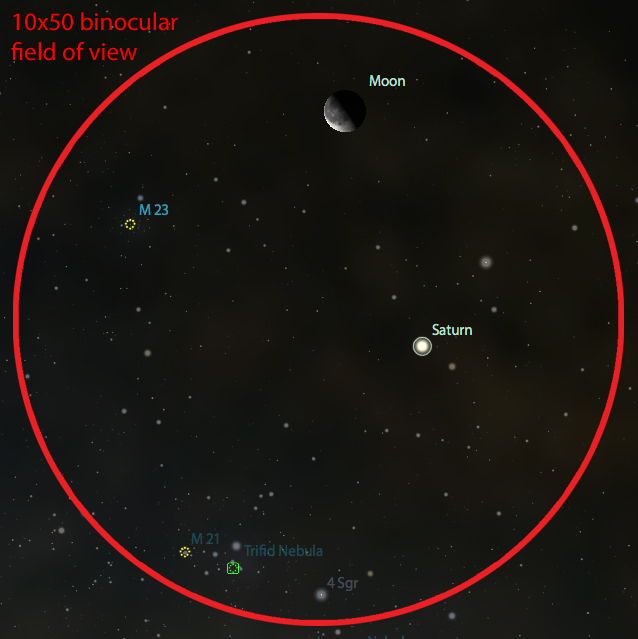

Saturn: Saturn continues it slow movement through Sagittarius this month, rising over the southeastern horizon just after 2:15 a.m. on March 1 and around 1:15 a.m. on the 31st. Saturn and the waning crescent Moon make for a close pair on March 20. Messier 23 will make for a small triangle in binoculars. The nebulae M21 and M20 can even be placed within the binocular field of view this night, but they will be very difficult to identify due to the brightness of the Moon.

ISS And Other Bright Flyovers

Satellite flyovers are commonplace, with several bright passes easily visible per hour in the nighttime sky, yet a thrill to new observers of all ages. Few flyovers compare in brightness or interest to the International Space Station. The flyovers of the football field-sized craft with its massive solar panel arrays can be predicted to within several seconds and take several minutes to complete.

The ISS is going to be an morning object until near the end of March. All of the morning sessions, from the 1st to the 23rd, fall into a window between 4:45 a.m. and 6:45 a.m., including double flyovers on the 18th, 20th, and 22nd. The "extremely" bright flyovers will be just that, with several expected to out-compete our late-evening Venus. At the end of the month, the ISS returns to the early evening, including double flyovers on the 29th and 31st. Simply go out a few minutes before the start time, orient yourself, and look for what will at first seem like a distant plane.

ISS fly-bys

| Date | Brightness | Approx. Start | Start Direction | Approx. End | End Direction |

| 3/1 | moderately | 6:05 AM | S/SW | 6:11 AM | E/NE |

| 3/3 | extremely | 5:56 AM | SW | 6:03 AM | E/NE |

| 3/4 | very | 5:05 AM | S/SW | 5:10 AM | E/NE |

| 3/5 | extremely | 5:48 AM | W/SW | 5:54 AM | NE |

| 3/6 | extremely | 4:57 AM | SW | 5:01 AM | E/NE |

| 3/7 | very | 5:39 AM | W | 5:45 AM | NE |

| 3/8 | extremely | 4:49 AM | N/NW | 4:52 AM | NE |

| 3/9 | moderately | 5:31 AM | W/NW | 5:36 AM | NE |

| 3/10 | moderately | 4:40 AM | N/NW | 4:43 AM | NE |

| 3/11 | somewhat | 5:22 AM | NW | 5:27 AM | NE |

| 3/12 | somewhat | 5:32 AM | N | 5:34 AM | NE |

| 3/13 | somewhat | 6:13 AM | NW | 6:18 AM | NE |

| 3/14 | somewhat | 5:23 AM | N | 5:25 AM | NE |

| 3/15 | somewhat | 6:05 AM | NW | 6:10 AM | E/NE |

| 3/16 | somewhat | 5:14 AM | N | 5:17 AM | NE |

| 3/17 | moderately | 5:56 AM | NW | 6:01 AM | E |

| 3/18 | extremely | 6:39 AM | NW | 6:45 AM | E/SE |

| 3/18 | somewhat | 5:05 AM | N | 5:08 AM | E/NE |

| 3/19 | very | 5:47 AM | NW | 5:52 AM | E |

| 3/20 | extremely | 6:30 AM | W/NW | 6:36 AM | SE |

| 3/20 | moderately | 4:56 AM | N/NE | 4:59 AM | E |

| 3/21 | extremely | 5:39 AM | NW | 5:43 AM | E/SE |

| 3/22 | moderately | 6:21 AM | W | 6:26 AM | S |

| 3/22 | moderately | 4:48 AM | E | 4:51 AM | E/SE |

| 3/23 | extremely | 5:31 AM | S/SW | 5:34 AM | S/SE |

| 3/26 | moderately | 9:05 PM | S/SW | 9:07 PM | S/SW |

| 3/27 | very | 8:13 PM | S | 8:17 PM | E |

| 3/28 | extremely | 8:56 PM | W/SW | 9:00 PM | NE |

| 3/29 | extremely | 8:03 PM | SW | 8:09 PM | E/NE |

| 3/29 | moderately | 9:40 PM | W | 9:42 PM | N/NW |

| 3/30 | very | 8:46 PM | W | 8:52 PM | NE |

| 3/31 | extremely | 7:53 PM | W/SW | 8:00 PM | NE |

| 3/31 | somewhat | 9:31 PM | W/NW | 9:34 PM | N/NE |

Predictions courtesy of heavens-above.com. Times later in the month are subject to change – for the most accurate weekly predictions, check spotthestation.nasa.gov.

Meteor Showers: No Major Showers This Month

As has been discussed in previous articles, meteor showers are the result of the Earth passing through the debris field of a comet or asteroid. While the orbits of scores of these objects bring them close to Earth's orbit, a limited number produce enough debris to produce significant meteor shower activity. February and March mark yearly lulls in major meteor shower activity, with the next prominent shower being the Lryids that occur in April. The astronomy community recognizes many minor showers that are predictable in their timing and are predictably unimpressive. Those interested in seeing a full list should check out the American Meteor Society meteor shower calendar.

Learn A Constellation: Ursa Major

For the first time in this series, we turn our constellation attention to the north. Standing to the northeast and nearly upright on its handle in the late evenings in March is the Big Dipper. In what might be the original instance of "let's take this argument outside," the Big Dipper and Orion have vied for the title of "most famous group of stars" among the amateur astronomy community for as long as people have needed reason to argue. Once pointed out, the Big Dipper is unforgettable, making it an ideal anchor to begin one's hobby as a lifelong star-hopper. As a place to spend the evening observing, the Big Dipper and its surroundings offer a great location to discover a number of interesting astronomical objects.

The Big Dipper, bright and famous as it is, is NOT a constellation. It exists as the torso and tail of the constellation Ursa Major, "The Great Bear." The Big Dipper is one of a handful of widely recognized groups of stars called "asterisms," which one can loosely define as "any group of stars that aren't defined as a constellation." It would be a Herculean task to propose any changes to the 88 modern constellations, but you are welcome to define any group of stars that jump out at you as an asterism – and authors have done so in astronomy books as aids to learning the locations of stars and other objects in the nighttime sky.

The ties that bind Ursa Major to the history of civilizations in the Northern Hemisphere are as much a wonder to behold as the stars themselves. The Romans recognized Ursa Major as a bear, it is one of the few groups of stars with Biblical citation, and tribes and civilizations throughout central and northern Europe up through Scandinavia recognized this star grouping as a bear. Closer to our home, the Iroquois, Algonquian, and Lakota also recognized Ursa Major as a bear early in their star lore. There are compelling arguments that this continental meta-drift is *not* just coincidence, but might be part of a shared oral tradition of nomadic peoples that goes back some 13,000 years to the early population of North America through Beringia, the Bering Strait Land Bridge that existed between Russia and Alaska during the last Ice Age. If true, this would place Ursa Major up there with Orion and Taurus as a *very* old star group.

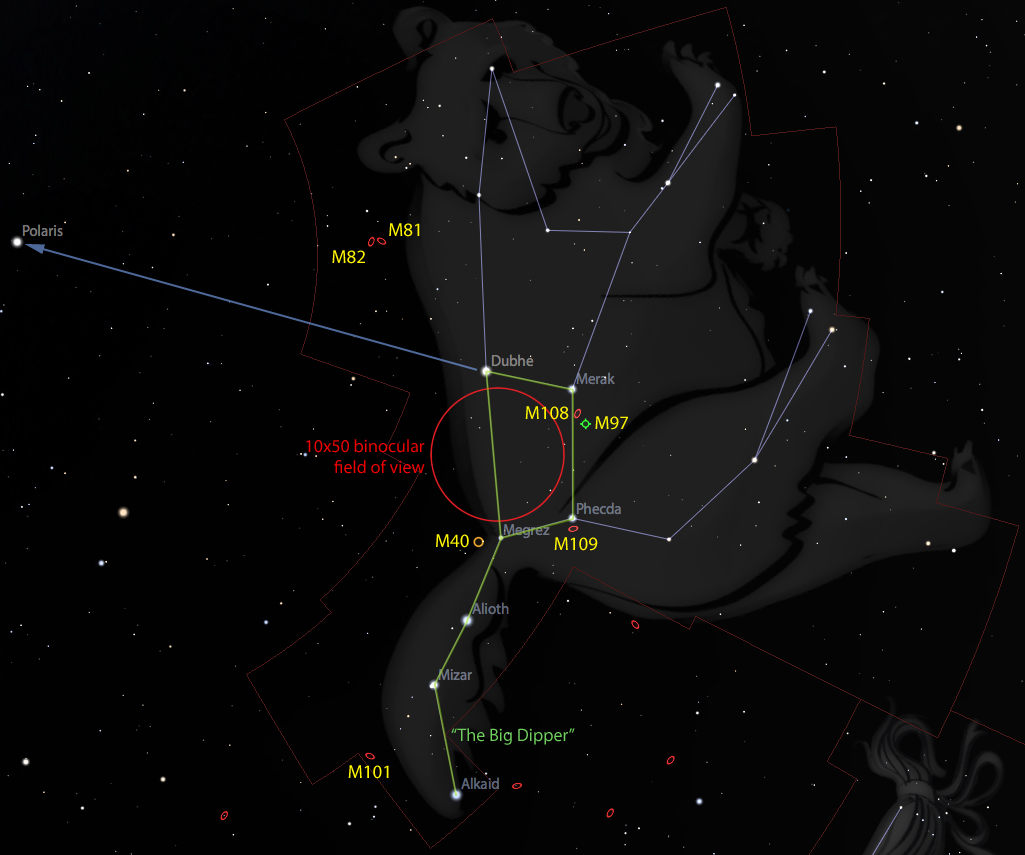

Like the belt, shoulder, and knee stars of Orion, one can't help but see the trees from the forest by spying the Big Dipper before the dimmer stars of Ursa Major. The three handle stars, Alkaid, Mizar, and Alioth, connect at the dimmer star Megrez to the remaining bowl stars Dubhe, Merak, and Phecda.

Turning our attention to the middle of the handle, a fun game to play at public observing sessions is to ask "How many stars do you see at Mizar?" Those with good vision will see two – Mizar and its dimmer companion Alcor. The history of what follows is not set in stone, but is not really in dispute either – the observation of Mizar and Alcor was used by the Roman Army as an eye test for soldiers. Those who could see both had excellent vision and were candidates for lookouts. Following that logic, those who could only see Mizar were assured never to see a big battle from a safe distance. I suspect that those who couldn't see Mizar either were assured never to see a battle from behind those who could. Alcor and Mizar turn out to be much more complicated than just a simple pair – Mizar is, in fact, a double-double! Magnification reveals Mizar to be a bright pair of stars, while professional equipment reveals each of these stars to themselves be a pair of closely-spaced stars, all bound gravitationally. The dimmer Alcor is itself a binary, making for a combined grouping of six stars.

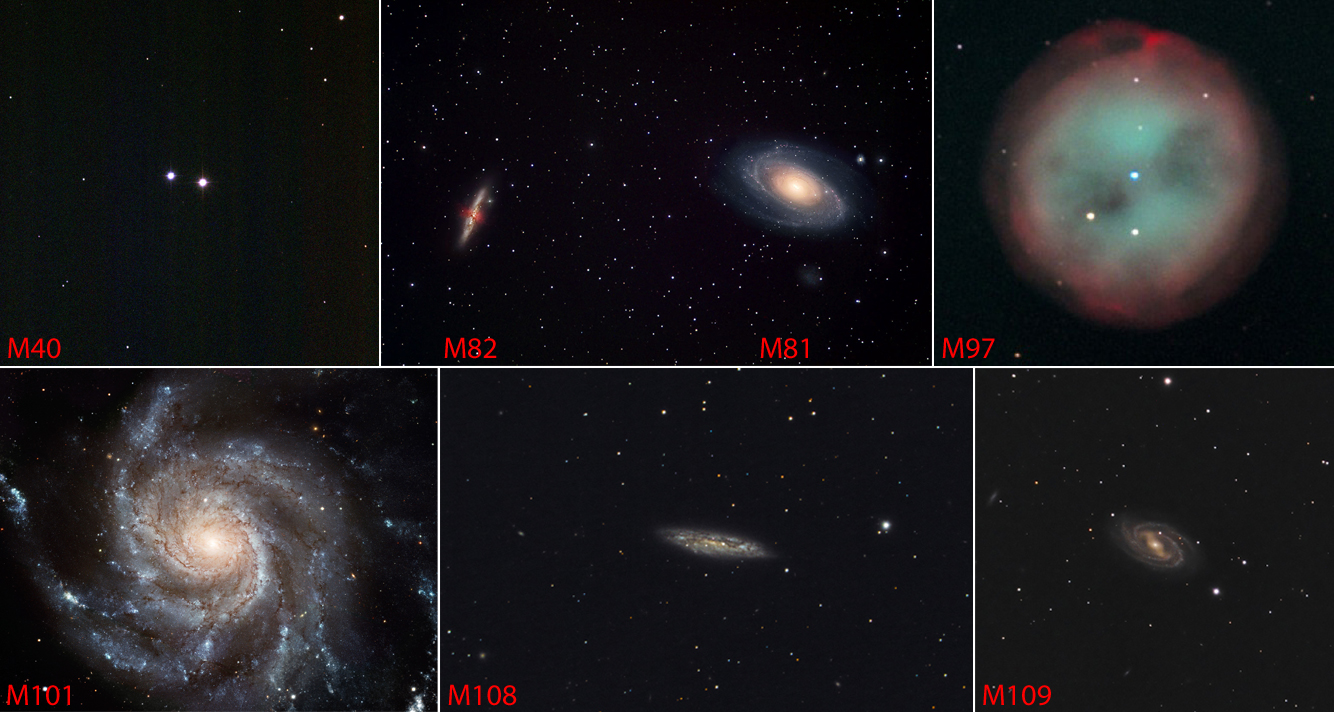

Within the borders of this massive constellation reside seven Messier Objects. M40 is a double star that very clearly doesn't seem to be a fuzzy object. Its identification as a Messier Object has been labeled by some as "Messier's greatest mistake." M81 and M82 are a pair of gravitationally-interacting galaxies beyond the bowl and above the front shoulder of Ursa Major. M97, the Owl Nebula, is well within the field of view of Merak in binoculars – but you will need very dark skies and excellent dark adaptation to ever see this object. The Pinwheel Galaxy, M101, is just at the edge of 10×50 binoculars with Mizar placed at one edge of your field of view, but is bright enough for binoculars. Galaxies M108 and M109 round out the Messier list along the bottom of the bowl. Far from street lights and the Moon, these seven are all possible to see with good dark adaption, but patience and a reduced expectation of their visual quality is key. In all seven cases, you may find that your hands are not steady enough to easily see these wispy objects under magnification. Even for binocular viewing, I recommend a decent tripod and binocular tripod mount to improve your views.

Dr. Damian Allis is the director of CNY Observers and a NASA Solar System Ambassador. If you know of any other NY astronomy events or clubs to promote, please contact the author.

Original Posts:

- https://www.newyorkupstate.com/outdoors/2017/02/upstate_ny_stargazing_in_march_messier_marathon_and_the_lunar_occultation_of_ald.html

- https://www.syracuse.com/outdoors/2017/02/upstate_ny_stargazing_in_march_messier_marathon_and_the_lunar_occultation_of_ald.html

Tags: